Guide Hall: A Comprehensive Overview

Guide Halls, embodying civic and academic purpose, represent significant architectural achievements, fostering collaboration and reflecting diverse styles throughout history․

Historical Significance of Guide Halls

Guide Halls emerged as crucial spaces reflecting societal shifts and evolving educational/civic needs․ Initially conceived to facilitate focused interaction – like the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s need for interdisciplinarity in 1936 – they quickly became symbols of progressive thought and collaborative spirit․

The construction of these halls often coincided with periods of significant urban development and modernization, as exemplified by Boston City Hall’s 1968 unveiling․ They weren’t merely buildings; they represented a commitment to public service and a tangible expression of civic pride․

Stockholm City Hall, completed in 1923, further illustrates this point, showcasing national identity through architectural style and craftsmanship․ These structures served as backdrops for pivotal historical moments, solidifying their place within a city’s collective memory and cultural landscape․

Early Origins and Development

The genesis of Guide Halls can be traced to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, driven by a growing need for dedicated spaces supporting specialized disciplines․ The Harvard Graduate School of Design’s establishment in 1936, necessitating a new home beyond Robinson and Hunt Halls, exemplifies this developmental phase․

Early designs prioritized functionality, aiming to break down traditional departmental silos and encourage cross-pollination of ideas․ This focus on interdisciplinarity became a defining characteristic․ Simultaneously, civic halls, like those emerging in burgeoning cities, were intended to centralize administrative functions and enhance public access․

Initial construction often utilized readily available materials – stone, brick, and emerging concrete technologies – reflecting the prevailing architectural trends․ These early iterations laid the groundwork for the more ambitious and stylistically diverse Guide Halls that would follow․

The Role of Architecture in Guide Hall Design

Architecture plays a pivotal role in shaping the identity and functionality of Guide Halls, extending beyond mere structural provision․ The design consciously aims to embody the institution’s values – collaboration, innovation, and civic responsibility․ Spaces are often conceived to be open and inviting, fostering interaction between students, faculty, and the public․

The deliberate choice of materials, spatial arrangements, and aesthetic styles communicates a sense of purpose and prestige․ Boston City Hall’s brutalist façade, while controversial, exemplifies a bold architectural statement reflecting civic power․ Conversely, Stockholm City Hall’s blend of National Romanticism and Renaissance influences conveys Swedish heritage and craftsmanship․

Ultimately, the architecture of a Guide Hall isn’t simply a container for activity; it actively participates in shaping the experiences within․

Key Architectural Styles Found in Guide Halls

Guide Halls showcase a diverse range of architectural styles, reflecting evolving design philosophies and cultural contexts․ Brutalism, exemplified by Boston City Hall, utilizes raw concrete and imposing forms to project strength and civic authority․ In contrast, National Romanticism, prominent in Stockholm City Hall, draws inspiration from local traditions and natural landscapes, employing red brick and ornate detailing․

Renaissance influences often appear alongside National Romanticism, adding a layer of classical elegance․ Modernism, as seen in some Guide Hall constructions, prioritizes functionality, clean lines, and the use of industrial materials․ Gund Hall at Harvard embodies this approach․

These styles aren’t mutually exclusive; many Guide Halls blend elements, creating unique architectural expressions․

Brutalism and Civic Architecture Examples

Brutalism, a dominant force in mid-20th century civic architecture, is powerfully represented by Boston City Hall․ Completed in 1968, its austere concrete façade and imposing scale aimed to convey governmental strength and transparency, though it sparked considerable debate․ The design, by Kallmann McKinnell and Knowles, intentionally rejected ornamentation, focusing instead on the raw materiality of concrete․

This style often featured repetitive modular elements and exposed structural components․ While sometimes criticized for its coldness, Brutalism sought to create honest and functional public spaces․ Other examples of Brutalism in civic buildings demonstrate a similar commitment to bold forms and unadorned surfaces, reflecting a post-war desire for pragmatic design․

National Romanticism and Renaissance Influences

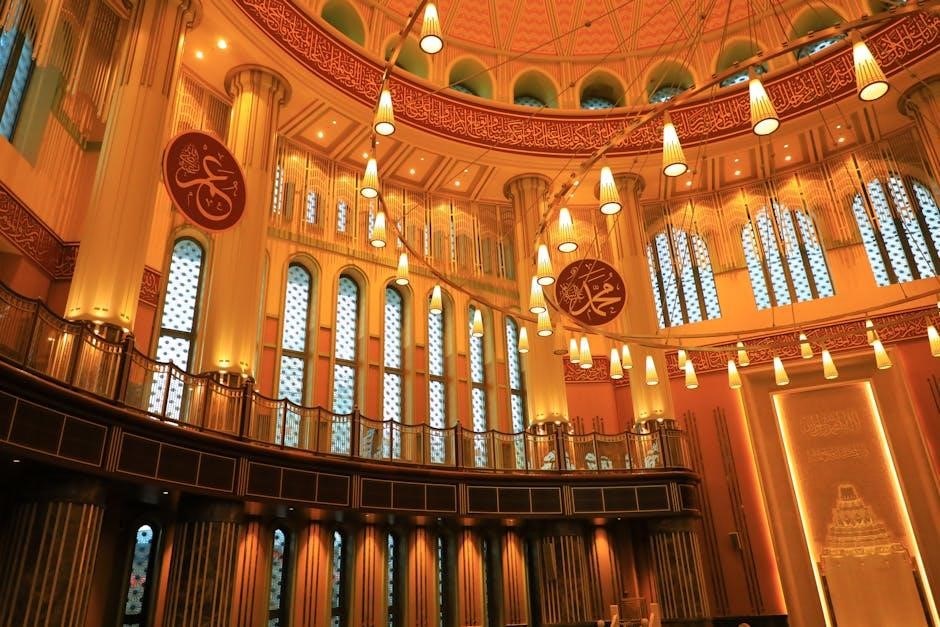

Stockholm City Hall (Stadshuset), completed in 1923, beautifully exemplifies the fusion of Swedish National Romanticism and Renaissance architectural principles․ Architect Ragnar Östberg masterfully blended these styles, creating a distinctly Swedish civic landmark․ The building’s design draws inspiration from historical Swedish castles and palaces, incorporating elements like towers, courtyards, and decorative brickwork․

Renaissance influences are evident in the symmetrical layout, arched windows, and ornate detailing․ Constructed with over eight million red bricks, the Stadshuset showcases exceptional craftsmanship and a strong sense of national identity․ This harmonious blend resulted in a building that is both grand and intimately connected to Swedish history and cultural heritage, serving as a powerful symbol of civic pride․

Modernism in Guide Hall Construction

Boston City Hall, built in 1968 by Kallmann McKinnell and Knowles, stands as a prominent example of Brutalist modernism in civic architecture․ Its austere façade and imposing concrete structure represent a deliberate departure from traditional architectural styles․ The building’s design prioritizes functionality and a bold, uncompromising aesthetic, reflecting the modernist ideals of the era․

Similarly, Gund Hall at Harvard University, completed in 1972, embodies modernist principles through its use of exposed concrete and geometric forms․ These structures showcase a rejection of ornamentation in favor of raw materials and clear lines․ While often controversial, these modernist guide halls aimed to create spaces that were both efficient and expressive of a new architectural vision, influencing subsequent generations of architects;

Notable Guide Hall Examples Worldwide

Gund Hall at Harvard University, designed for the Graduate School of Design, exemplifies a space fostering interdisciplinarity․ Boston City Hall, a Brutalist landmark, showcases civic architecture’s bold aesthetic, though often debated for its starkness․ These buildings represent distinct approaches to creating functional and symbolic spaces․

Stockholm City Hall (Stadshuset), completed in 1923, offers a contrasting example, blending Swedish National Romanticism with Renaissance influences․ Constructed with over eight million red bricks, it embodies Swedish craftsmanship and civic pride․ Each hall—Gund, Boston, and Stockholm—demonstrates how guide halls globally reflect unique cultural contexts and architectural philosophies, serving as vital centers for governance, education, and community․

Gund Hall, Harvard University

Gund Hall, completed in 1972, serves as the home for Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design (GSD)․ Established in 1936, the GSD aimed to unite Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and City Planning, necessitating a dedicated space․ By the early decades, Robinson and Hunt Halls proved insufficient for the growing school and its collaborative ambitions․

Gund Hall was specifically designed to facilitate this interdisciplinarity, encouraging interaction between different design disciplines․ Its design prioritizes open studio spaces and communal areas, fostering a dynamic learning environment․ The building itself is a significant example of modern architectural thought, reflecting the GSD’s commitment to innovative design principles and practices․

Boston City Hall

Boston City Hall, constructed in 1968 by Kallmann McKinnell and Knowles, stands as a prominent – and often debated – example of Brutalist civic architecture․ Located on a windswept plaza in downtown Boston, its austere façade and imposing concrete structure have garnered both praise and criticism over the years․

The building represents a deliberate departure from traditional architectural styles, embracing a bold and unapologetic aesthetic․ Its design prioritizes functionality and a sense of civic gravitas, aiming to embody the power and responsibility of local government․ Despite its controversial reception, Boston City Hall remains a significant landmark, sparking ongoing discussions about the role of architecture in shaping public space and civic identity․

Stockholm City Hall

Stockholm City Hall (Stadshuset), completed in 1923 after twelve years of construction, is a magnificent example of Swedish National Romanticism blended with Renaissance influences․ Architect Ragnar Östberg masterfully combined these styles to create a building that embodies Swedish craftsmanship and civic pride․

Constructed with over eight million red bricks, the Stadshuset is not merely a functional building but a powerful symbol of Swedish identity․ Its design incorporates intricate details and symbolic ornamentation, reflecting the nation’s history and cultural values․ The building serves as a venue for the Nobel Prize banquet, further cementing its status as a national treasure and a globally recognized landmark, showcasing exceptional architectural design․

Construction Materials and Techniques

Guide Hall construction historically favored durable and aesthetically pleasing materials, with stone and brick being prominent choices for their longevity and visual appeal․ These materials offered both structural integrity and opportunities for ornate detailing, reflecting the civic importance of these buildings․

However, the 20th century witnessed a significant shift with the incorporation of concrete and wood․ Concrete allowed for bolder, more modern designs, exemplified by Brutalist structures, while wood provided warmth and a connection to natural elements․ Modern techniques, alongside traditional masonry, enabled architects to realize increasingly complex and ambitious designs, shaping the functional and aesthetic qualities of Guide Halls․

Use of Stone and Brick

Historically, Guide Halls frequently employed stone and brick due to their inherent durability and aesthetic qualities․ These materials conveyed a sense of permanence and civic authority, essential for buildings intended to serve as centers of governance or learning․ The selection often reflected regional availability, influencing the specific type of stone or brick used – from local limestone to distinctive red bricks․

Stockholm City Hall, for instance, utilized over eight million red bricks, showcasing the material’s capacity for large-scale construction and visual impact․ Skilled masonry techniques were crucial, allowing for intricate detailing and robust structural support․ Stone and brick weren’t merely building components; they were statements of craftsmanship and enduring civic pride․

Incorporation of Concrete and Wood

The 20th century witnessed a shift in Guide Hall construction, with concrete and wood becoming increasingly prominent materials․ Concrete offered unprecedented design flexibility and structural strength, enabling the bold forms seen in modernist examples like Boston City Hall․ Its use signified a departure from traditional masonry, embracing industrial innovation․

Wood, while historically used, found renewed application in interior finishes and structural elements, providing warmth and contrasting with concrete’s austerity․ Valentino Architects’ recent project demonstrates the continued relevance of wood, blending it with existing stone structures․ These materials allowed architects to balance functionality with aesthetic considerations, shaping spaces conducive to collaboration and civic engagement․

Functionality and Purpose of Guide Halls

Guide Halls historically served, and continue to serve, dual purposes: facilitating focused work and fostering broader civic interaction․ Institutions like Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, housed in Gund Hall, were specifically designed to encourage interdisciplinarity between Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and City Planning․ This collaborative spirit demanded spaces adaptable to diverse activities․

Beyond academia, structures like Stockholm City Hall exemplify a Guide Hall’s role as a center for civic engagement, hosting ceremonies and representing national pride․ These buildings aren’t merely containers for activity; their design actively promotes interaction and a sense of community, embodying a commitment to public service and shared purpose․

Facilitating Collaboration and Interdisciplinarity

The core design principle behind many Guide Halls centers on breaking down traditional departmental silos, actively promoting collaboration․ Gund Hall at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) exemplifies this, created in 1936 to unite previously separate schools of Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and City Planning․

This need for interdisciplinary exchange drove the GSD to seek a new home, recognizing that its original facilities hindered the desired synergy․ Successful Guide Halls prioritize open layouts, shared spaces, and informal meeting areas, encouraging spontaneous interaction between students and faculty from diverse fields․ The very structure embodies a commitment to holistic problem-solving․

Serving as Centers for Civic Engagement

Many Guide Halls, particularly those functioning as City Halls, are intentionally designed to be focal points for community interaction and democratic processes․ Boston City Hall, despite its controversial Brutalist aesthetic, was conceived as a transparent and accessible seat of government, aiming to connect citizens directly with their elected officials․

These structures often house public meeting rooms, council chambers, and spaces for community events, fostering a sense of civic ownership and participation․ Stockholm City Hall, with its grand halls and symbolic spaces, similarly serves as a venue for official ceremonies and public gatherings, reinforcing its role as a center for Swedish civic pride and national identity․

Preservation and Modernization of Guide Halls

Maintaining the historical integrity of Guide Halls while adapting them to contemporary needs presents a significant challenge․ Balancing preservation efforts with the demands of modern functionality requires careful consideration and innovative solutions․ Adaptive reuse, transforming historic spaces for new purposes, is a common approach․

This often involves integrating modern systems – HVAC, accessibility features, and technology – without compromising the building’s original character․ The goal is to ensure these structures remain relevant and useful for future generations, acknowledging their history while accommodating present-day requirements․ Successful modernization respects the architectural significance while enhancing usability․

Balancing Historical Integrity with Contemporary Needs

Successfully updating Guide Halls demands a delicate equilibrium between respecting their original design and incorporating modern functionalities․ Preservationists and architects face the challenge of integrating new systems – like updated HVAC, accessibility features, and advanced technology – without diminishing the building’s historical character or aesthetic value․

This often involves employing reversible interventions, utilizing materials sympathetic to the original construction, and carefully concealing modern infrastructure․ The aim isn’t simply to restore, but to revitalize, ensuring these structures remain functional and relevant while honoring their history and architectural significance for generations to come․

Adaptive Reuse of Historic Guide Halls

Adaptive reuse presents a compelling strategy for preserving Guide Halls, transforming them to serve new purposes while retaining their architectural essence․ This approach breathes new life into these structures, avoiding demolition and celebrating their inherent value․ Former civic centers or academic buildings can be reimagined as cultural hubs, mixed-use developments, or even residential spaces․

Successful adaptive reuse requires thoughtful planning, respecting the original building’s layout and features․ It’s about finding innovative ways to integrate contemporary needs without compromising historical integrity, often revealing hidden architectural details during the renovation process, and ensuring a sustainable future for these landmark buildings․